Protagonist (Ravic) is a skilled German surgeon who lost citizenship in Nazi times; he's illegally performing surgeries for two well-known (but not as talented) Paris surgeons. Can't get citizenship elsewhere. Action occurs between the wars. He meets various other stateless folks; it's an interesting/effective take on the way they lived. Occasional deportations. He lives in a hotel that caters to folks like this. Encounters an actress. I always enjoy Remarque's stuff, though didn't like this as much as All Quiet on the Western Front or Three Comrades.

Too often I read a book, and then quickly forget most of it (or all of it, for less memorable works). I'm hoping this site helps me remember at least something of what I read. (Blog commenced July 2006. Earlier posts are taken from book notes.) (Very occasional notes about movies or concerts may also appear here from time to time.)

"To compensate a little for the treachery and weakness of my memory, so extreme that it has happened to me more than once to pick up again, as recent and unknown to me, books which I had read carefully a few years before . . . I have adopted the habit for some time now of adding at the end of each book . . . the time I finished reading it and the judgment I have derived of it as a whole, so that this may represent to me at least the sense and general idea I had conceived of the author in reading it." (Montaigne, Book II, Essay 10 (publ. 1580))

Thursday, December 10, 2020

Monday, November 23, 2020

Say Nothing: A True Story of Murder and Memory in Northern Ireland (Patrick Keefe, 2019)

Book club selection (via POC; session held (via Zoom) November 22, 2020).

specific discussion about a common situation - boundaries are determined by conquest, power

within the boundaries are groups that may or may not get along well. active favoritism of group in power over another. throughout history - restrictions on Jews in Christian countries; restrictions on Christians in Islamic countries. many examples. Blacks in U.S.

not feasible to unmix the populations, though tried very hard to do this following WWI and WWII. but property ownership, tradition, where to go anyway.

then how does disadvantaged group react? at some point negotiation seems insufficient, and violence starts. and hunger strikes. it's a power relationship.

and it leads to progress, right? (despite the awfulness) this only applies in democracies with a free press - good luck trying this elsewhere

~20-year cycle - a generation forgets the horrors, then a subsequent generation repeats it

endless and unhelpful tendency to glamorize those coming from the left. Che, Castro - bigots, totalitarians in their own right - still on T-shirts and posters, somehow!

IRA in the same light. the sisters.

outright criminal acts in service of the cause - somehow considered excusable by way too many

at outset I worried about author's tendency to use language like today - anyone from the right is a reactionary, those on the left are sympathetic if not cool. but ended up very well balanced

really helpful look at the toll from a macro level, and on the individual level

Wednesday, November 11, 2020

Dandelion Wine (Ray Bradbury, 1957)

Didn't know Bradbury wrote this kind of thing; suggested by (borrowed from) Paul Jr; another book that I wouldn't necessarily seek out, but much enjoyed.

Bradbury is building stories out of his Ohio childhood.

A reason for the recommendation - and it turns out to be correct - is that Bradbury had an ear for a life very much like mine as I grew up in the 50s and 60s. There are some differences - he's a decade or two earlier, and lives in the town proper - but there were many-many times while reading that I would have a memory, typically quite pleasant, of something long-forgotten.

As usual - I liked some stories more than others - that's not a problem. A little dramatic with the "ravine" angle. Perhaps a little overly hero-worship-ish with the grandparents - but that's kind of how we felt, too. Ideas about getting older; about kids getting wiser (and perhaps correspondingly sadder).

Kids sitting around listening to the grown-ups converse in the evenings - Bradbury describes it as the "soundtrack" of childhood in those days - I thought that was very observant. (And find myself using the phrase.)

Tuesday, October 20, 2020

Persepolis (Marjane Satrapi , 2004)

(160 pp (graphic novel))

Book club selection (via Nicole; session held (via Zoom) mid-October 2020).

liked the tone of the discussion about the revolution - effective at ferreting out the hypocrisy

attitude of many toward Islam today reminds of Communism in 30s-50s, and still to this day. Wilful blindness. example: so intent on supporting Palestinians (or some vision of what that might stand for?) against imperialist Israel that refuse to see that Palestinians (or aspects Islamism writ larger) has issues (like everything). Very strange.

A religion founded on conquest and "end of time" religious principles, sometimes this bleeds through.

Iran as a political mess - poor, illiterate. Tehran no particular history.

tough sequence post WWI: shah-revolution-iran/iraq war

didn't so much like: author felt very superior to other women she viewed as less enlightened . . . hmmm . . . associate freedom with sex and drugs, next stop is the analyst. Husband as someone they all knew wouldn't last - huh?

didn't really care about her relationship travails

useful to see ourselves in these ostensibly extreme situations

when everything becomes political . . . how much do we differ? government control of schools, ideology, statue toppling, street mobs

after tracking this pretty closely with govt major and law school - now totally (and happily) keeping distance from politics

cycle when something like this lasts >1 generation . . . folks grow up in it . . . how to change?

you get a scenario where an all-encompassing $6T govt is claimed to hinge on a single SCt seat . . . each of the last dozen vacancies was claimed to determine the fate of the republic . . .

deep orthodoxy in US; % of educators with identical political views

things that resonated: tourist to Caspian; Reghabis leaving before borders closed

good book, thought-provoking

Tuesday, October 06, 2020

Catch-22 (Joseph Heller, 1955)

(453 ppp)

Yossarian is deservedly a classic character; the book is also a classic.

I found the schtick a bit much in the early going, but grew to like the book. Yossarian wasn't such a bad/thoughtless guy.

Recommended by (and borrowed from) CPG.

Friday, September 25, 2020

The Border Trilogy (Cormac McCarthy, 1992 - 1998)

All the Pretty Horses (302 pages)

16-year-old John Grady Cole (protagonist) and best friend (Rawlins) depart for Mexico in 1949 - little to keep them home in Texas as ranch where protagonist grew up was being sold following his grandfather's death and as part of his parents splitting. They intend to find work on a ranch and see what develops. Encounter Blevins (and his too-good horse) while crossing into Mexico; he seems to be about 13. Blevins's horse is stolen; they help him steal it back; this has some consequences. Cole and Rawlins find work on a huge ranch - old school Mexican wealth. Cole in particular has superior skills with horses and gets promoted. Adventures; Rawlins back to Texas and Cole follows briefly.

The Crossing (426 pages)

Story line starts just before WWII. Liked it better. Billy Parham obsessed with wolves from earliest; ends up trapping one that had strayed up to New Mexico from Mexico; decides to return it. Long discussions of trapping technique; many adventures escorting a wolf through this kind of terrain.

Eventually returns to NM to find out his parents were killed (and horses stolen by killers); picks up his younger brother (Boyd) and they head into Mexico, with an idea of retrieving the horses; they encounter lots of adventures. Billy makes a third trip to Mexico, alone.

Cities of the Plain (292 pages)

Story line starts in 1952. John Grady Cole and Billy Parham (protagonists of the first two novels in the trilogy) are working on a ranch in New Mexico - near Mexican border, El Paso. Their way of life is dying out; land being taken by defense department. John Grady falls in love but problems. Epilogue shows Billy as an old man.

____________________

The trilogy is very much worth reading - I much enjoyed. We've lived in Arizona since 1986 and it's easy to be captivated by author's description of SW scenes. So much about horses - I personally don't know anything about them, but the descriptions are continually interesting. Youthful protagonists seem a bit too accomplished, but that's a minor criticism. Northern Mexico in hard times; in book 2 with its late 1930s setting - many folks with vivid recall of the messy 1910 revolution and its even messier aftermath.

Wonderful discussions of the countryside; what rural Mexico may have felt like in those days; without romanticizing - some rough characters, rule of law more an idea than reality. Generosity of poor people. Lead characters are interesting.

Tuesday, September 08, 2020

Augustus (John Williams, 1972)

Story of Augustus (Octavius) is told in epistolary form. Gave me a better feel for this era. Hadn't realized (or had forgotten) that Augustus started with a triumvirate (Marc Antony, Lepidus); that his ascension was a rather close-run affair. Brutus; Cassius; Livy; Cicero. Cleopatra.

His three early friends, especially Marcus Agrippa.

Isolation, perhaps unhappiness, in this retelling of the holder of so much power. Remarkably long life, established the role of "emperor" as a real thing in Rome; established meaningful stability.

More focus on his daughter (Julia) than I needed - she was harmed by availability to power more than Octavius - hard times for talented women in imperial families (or elsewhere, I suppose).

Useful counterpoint to Shakespeare's telling of this story.

Thursday, August 27, 2020

City of Djinns - A Year in Delhi (William Dalrymple, 1993)

Written in 1993; would be interesting to know how well it's aged. Author lives in Delhi for a year and builds his book around it; goes through weather cycle; describes various eras in the city's history, generally working backward.

Describes Partition as source of huge change - population doubled in ~10 years as Sikhs, Punjabis move into Delhi. Partition stories. His landlady was Sikh. Larger Islamic presence pre-Partition.

Urdu/Mughal tradition . . . post-Partition remainers consider their difference from Punjabis and others stronger than Hindu/Muslim split (really?) After Partition, Urdu tradition is concentrated in old Delhi; fading. Punjabis considered provincials; better at commerce. This part of the book perhaps outdated.

Discussion then goes back to early days of Brits. They started in various areas in India but early Calcutta presence most relevant for Delhi. Sent folks up the Ganges in mid/late 18th century; difficult journey completed overland. Delhi already in decline - Persian invasion/massacre of 1739 perhaps the exclamation point - but Mughal authority still present (and ultimately usable by Brits). City had faded to something of a backwater after recent glory. Fraser/Scots as initial Brit presence - rough times, working to subjugate the countryside. They tend to "go native" but as 19th century progresses - more conservative Brit style takes over. Culminates in 1857 rebellion; things are going exactly backward: viewing natives as "the other." (Mixed race folk not accepted by either side.) Destruction in Delhi as punishment for 1857; followed by building process for New Delhi as center of Brit authority in this part of the country.

He wastes some time on Sufi and eunuch concepts - didn't seem worth it, but he was able to find remnants to interview so used the material.

Then more on Mughals. Aurangzeb details . . . 6th and last great Mughal emperor, died 1707. Poisonings, intrigue. Islamic fundamentalist for his times, created strains between Hindu and Muslim that flowered (supposedly the two were much more accepting of each other prior to this).

Delhi as Islamic since 12th century; Mughals show up 16th century. As book winds up, I like how he describes Islamic dominance as a six-century interlude; British as a far briefer incursion; now back to Hindu per millennia prior.

Concludes with discussion how the Mahabharata fits into Delhi's history - that part is interesting.

Sunday, August 23, 2020

Hymns of the Republic - The Story of the Final Year of the American Civil War (S.C. Gwynne, 2019)

Book club selection (via Zach; session held (via Zoom) 23 August 2020).

But in the end the book works quite well - much more focus on personalities (North and South); that requires some summarizing, if not shortcutting, given that extensive biographies exist on most of these folks; but it feels like a good/fair overview.

Discussion of some of the political points was useful; Lincoln's need to obtain votes from the border states; the 1864 election; race issues had a certain immediacy compared to today.

The armies learning to "dig in" in a more systematic way that influenced war-making for a long time - hadn't thought of that - look at Petersburg, especially. (Side thought: relatively little large-scale war happens after Civil War that tactics (perhaps, weaponry) to defeat trenches didn't develop (Spanish-American war; Franco-Prussian war; Russo-Japanese war; Boer war); perhaps this contributes to WWI trench stagnation, slaughter. Interesting to think it was taking shape here in the Civil War.

Discussion of early Washington DC - small, yucky. Interesting; it was a fairly new city without air conditioning.

U.S. Grant - gets a fair treatment, I think. Still thinking about how interesting his memoirs are.

Sherman - he and Grant got it, in terms of modern (total) war. Soldiers facing inevitable attrition rates; property destruction, etc. Nothing glorious about it anymore, if there ever was.

Greek fire was mentioned for the second book club selection in a row (Confederate plotting here that came to naught).

Tuesday, August 18, 2020

Slaughterhouse Five (Kurt Vonnegut, 1969)

I'm glad I read this, but I don't think I "get it" in terms of what the author is trying to do.

It's a story built around the WWII Dresden fire-bombing.

But mostly tracks the adventures of Billy Pilgrim - a rather strange fellow who ends up in the war, gets captured and sent to Dresden (where he survives because confined in a reinforced slaughterhouse), gets married to a wealthy spouse, runs (or perhaps "falls into") a thriving optometry practice, travels in time, and journeys to a faraway planet.

Anti-war; lots of clever writing; absurdist style; all that's fine.

But still.

Saturday, August 15, 2020

A Soldier of the Great War (Mark Helprin, 1991)

There are early passages that seem to be just floating out there, but author does a really good job of tying things together - sometimes with aspects I had forgotten over the course of hundreds of pages.

Quite a few fantasy touches - protagonist gets into multiple amazing situations, survives incredible dangers, meets one elite person after the next; the whole Orfeo (he of the blessed sap) story line.

As a youngster - encounter with Austrian soldiers, princess (and her fat relative), gondola ride with stricken orchestra member; horsemanship and the neighbor's daughter; mountaineering with Rafi. The lawyer Giuliani (his father) Loves the family garden.

The kinds of conversations held by folks facing near-certain death; how they think of what might lie on the other side (or not); will I be remembered? Author does a good job on this.

Author's technique of not writing scenes all the way to a conclusion - just giving the reader enough to know what's going to happen and leaving it to imagination - then picking up the story line - this really works well, I liked it. Though he probably should have used the technique in the last half dozen pages.

Plenty of memorable characters - I liked Strassnitzky - the pacifist field marshal. A general on the winter line charged with sending the Italian troops up towards Innsbruck - does a great job talking about the absurdity of what they were doing.

Alessandro's life gives a vehicle for the author to meditate on the nature of religious faith, the nature of love - for family-of-origin, for war buddies, for wife and child - of course there are no hard answers to any of this, but he offers lovely, thought-provoking things about these topics.

Proust-type touches - how memory of important people and events stays with us; also Alessandro's training in aesthetics - seeing beauty, linking to works of art. Significant chunks of the story line revolve around a couple art works; interesting.

Tuesday, August 04, 2020

O Pioneers (Willa Cather, 1913)

“But you show for it yourself, Carl. I'd rather have had your freedom than my land.”

Carl shook his head mournfully. “Freedom so often means that one isn't needed anywhere. Here you are an individual, you have a background of your own, you would be missed. But off there in the cities there are thousands of rolling stones like me. We are all alike; we have no ties, we know nobody, we own nothing. When one of us dies, they scarcely know where to bury him. Our landlady and the delicatessen man are our mourners, and we leave nothing behind us but a frock-coat and a fiddle, or an easel, or a typewriter, or whatever tool we got our living by. All we have ever managed to do is to pay our rent, the exorbitant rent that one has to pay for a few square feet of space near the heart of things. We have no house, no place, no people of our own. We live in the streets, in the parks, in the theatres. We sit in restaurants and concert halls and look about at the hundreds of our own kind and shudder.”

Tuesday, July 28, 2020

The White Guard (Mikhail Bulgakov, 1925 but not allowed to be published until 1966)

Author wrote this wonderful, far more famous, work.

Bolsheviks ("Reds"), czarists ("Whites"), Ukrainian nationalists are fighting in various areas outside Kiev. German forces have been hanging around in the wake of Russia's surrender - and generally maintaining order in Kiev - but now are withdrawing (Germany having its own problems in late 1918.)

Deeply interesting look at such a messed-up time. White resources are limited and leadership feckless; Petlyura leads the Ukrainian forces into Kiev but the Reds are gaining strength. White efforts to resist Petlyura are less than feeble - mostly a few officers and cadets, with limited resources.

The family through whose eyes the story mostly is told: Alexei (doctor); Elena (their sister with the husband who leaves); Nikolka (younger brother - inexperienced cadet). They were friends with a few officers; a family member unexpectedly joins them. Neighbor downstairs is robbed.

Descriptions of Kiev in winter.

This being Bulgakov - several passages involving characters having dreams.

Per Wikipedia - Bulgakov is tracking the history of these times pretty closely (including the Petlyura character (who actually never appears in the story despite constant references)). I know very little about the details here, so much of this was new.

Turns out Bulgakov made this into a very successful stage play - supposedly seen often by Stalin - but he wasn't allowed to publish the book.

I liked it.

Wednesday, July 22, 2020

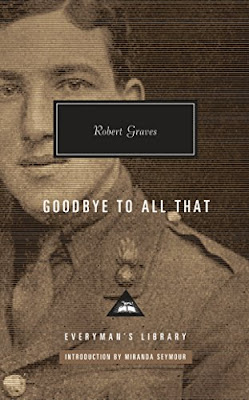

Goodbye to All That (Robert Graves, 1929 (using 1957 text))

(360 pages)

(360 pages)Essentially an autobiography of early part of author's life, though includes elements not originally written to be used as such. I don't know much about Graves, he was a very well-known poet and author.

By far the best part is the WWI discussion (also longest - book is much worthwhile just for this).

Starts with early family life; then author experiences English schoolboy life as someone who didn't fit in well. Rules/traditions in those days - stifling. Then gets into military and finds a lot of the same. (Not wired for military, but WWI breaks out just as graduating.)

Endless connections via family, school, military. The incredibly small world of Brit upper class. I keep thinking that this connectedness was a big factor in sustaining Brit ascendancy - idea-sharing, common values - small island with outsized influence for a very long time.

Develops close relationship with George Mallory, they go climbing; he is best man at author's wedding.

German relatives - visits in prewar, later they are fighting on the opposite side; this connection leads to some suspicions during the war.

Front line/trench discussions really good. I've also read a lot about this where it's part of a larger narrative in a novel (Parade's End, for example) or an overall history of the war (for example, this one by John Keegan); Graves's approach is different, effective - diary-style, where no compulsion to sacrifice details to a larger story arc. Reminds of the wonderful Isaac Babel military diary-sketches (also in that the writer isn't a military-type, at all).

Exciting times in front lines but he also has quite a few other roles in the military - training, supply stuff - some in England, some back of the front lines - assigned there because of wounds, and also because of what they then called neurasthenia - his nerves were shot. These discussions also interesting, in part because I've seen less of them.

As war winds down, Spanish flu kills mother-in-law; he travels on train with it. That discussion is interesting in these COVID-19 days.

Socialism seems attractive after the war, which made some sense at the time.

Recounts interactions with Wilfred Owen and a lot of poets I don't know, Thomas Hardy, T.E. Lawrence - I found myself not so interested in his reminiscences of meet-ups with famous folk.

Other postwar stuff - married, four kids, Oxford degree, takes a teaching position in Egypt.

Ends at age 33; epilogue reports that he lived in Majorca quite a bit; remarried and had four more children.

Tuesday, July 21, 2020

Abigail (Magda Szabo, 1970)

I picked this book because Hungary's positioning between the two world wars always seems like an interesting setting, and the review was favorable.

Then I became a little nervous that the plot might be too focused on life in a girls boarding school. And there was quite a bit of that, but it fit into the story line quite nicely and I ended up enjoying the book quite a bit.

Protagonist is the 14 year old daughter of a Hungarian army general; spoiled, willful, enjoying life in Budapest; sent off to a provincial boarding school without much explanation and has a hard time fitting in. Abigail is a statue that somehow seems to intervene when the girls have severe troubles.

Meanwhile the alliance with Hitler is going poorly, the Hungarian army is getting pummeled in the Stalingrad fighting, Germany is taking over in Hungary, tension and difficult decisions.

Author does a good job developing characters among the school girls, the faculty, etc.

Recommended.

Monday, July 20, 2020

The Kingdom of Copper (S.A. Chakraborty, 2019)

Book club selection (via Emily; session held (via Zoom) 19 July 2020).

Second in a trilogy; we had read the first as a book club selection.

Lots of action, actually violence - often rather heavy for my taste these days.

Mostly the same characters as in the first book.

Emphasis on tribal groups does remind of current political climate - where identity politics seem to attract votes - ugh.

The use of words and concepts from India, Persia, and what I'll call the Middle East is interesting.

The plot not so much. And I have trouble remembering what form of magic which characters can use, and what tribal characteristics apply.

Monday, July 06, 2020

The British Are Coming - The War for America, Lexington to Princeton, 1775-1777 (Rick Atkinson, 2019)

I've never read much about the Revolutionary War, not sure why. Hadn't realized there was so much action action prior to issuance of the Declaration of Independence.

Lexington, Concord stories (1775) - genuinely exciting; tough times for the Americans at Lexington but a sense of accomplishment in Concord.

The author's way of making many people (officers, rank and file, home front) come alive in just a few words; of supplying enough details (for example attaching numbers to supplies - gives a sense of scope); always without bogging down or losing the larger narrative. Readable, interesting.

I had never read much of anything about the 1776 campaign in the southern states (only recalling the cannon balls embedded in the palmetto fort) - mostly a costly diversion for British, interesting discussion.

Benedict Arnold was so talented, involved in so much up north.

Scope of the war was impressive - south, Canada, New York (where British had great successes in 1776, perhaps only wanting for follow-through) But the immense difficulties of sending an army across and sea, and supplying it.

In general, 1776 as a pretty dreary year for the Americans after the Declaration. But then Trenton and Princeton - crossing the Delaware on Christmas night, 1776 - this was a much more difficult, and important, undertaking than I had ever realized. Lots of information throughout on the Hessians (who happened to be the target at Trenton, unfortunately for their reputation).

The so-often-repeated error (committed here by the British) of assuming that the local population will rise up in support with just a little success and encouragement - this shows up in invasions in many locations and time periods.

A lot went wrong for England; quite a few decisions that were bungled; but the scope of England's late 18th-century international activities is really impressive.

The colonies as having so much to work out in terms of governance; such variety among them. An amazing intersection of ideas emerging in English colonies protected by oceans - a chance to work out governance in a new way.

Wednesday, June 17, 2020

Our Mutual Friend (Charles Dickens, serialized 1864-65)

Miserly old man (Harmon) makes fortune in dust business; breaks family bonds; creates odd incentives in his will; events follow.

Hexam and Riderhood families - working out a rough life on the waterfront - heavy stories. Charlie Hexam getting a chance at education; Lizzie getting a chance; the schoolmaster is intense. The honest public house owner.

Wilfer family - mother and younger daughter (Lavinia) - effectively comic (Bella is older daughter favored by Harmon the original old dust man). Wilfer father a "cherub."

Boffin family - loyal to Harmon; somewhat reminded of the Bleak House character (the guy who ran the shooting gallery).

John Rokesmith.

Lawyers Mortimer Lightwood and Eugene Wrayburn.

Inspector - reminds of Bottle from Bleak House.

Wegg - the "man of letters" - reading Decline and Fall to Boffin - not a nice person, but presented in an amusing way. Interested in contents of the dust mounds, enlists Venus.

Would-be aristocrats receive a lot of shots; lawyers not very well thought of, either.

Jewish character involved in money-lending business, portrayed sympathetically

I enjoyed throughout except for one significant oddity (weakness) in the plot (G.K. Chesterton's note (included as an Appendix) explains what happened, but don't check that until after finishing the novel). Notwithstanding - recommended.

[Gift from Paul Jr & Nedda]

Sunday, May 31, 2020

Arrival - Stories of Your Life and Others (Ted Chiang, 1990-2002)

Liked this; didn't love it. Notes on a few of the stories follow.

First story - about Tower of Babel - probably my favorite. I of course love the original Bible story - this is very creative in describing the tower construction - ending a bit of a letdown, not understanding the water business going in a circle.

"Story of Your Life" - per the Arrival movie - all the back-and-forth with the daughter who died in an accident. The idea of their written language as differing from verbal - didn't have to waste time with sequential-ness - that made a glimmer of sense as thinking of listening to a reader (or video/TV narrator) as compared to reading. Knowing the future. Interesting.

"Seventy-Two Letters" - trying to generate human life via automata; kabbalist; didn't care about anything in this story line. Hugo movie . . . don't know what the 72 letters/nomenclature thing refers to. Gilgamesh.

"The Evolution of Human Science" - just a few pages, something about metahumans taking over scientific research because humans can't keep up

"Hell Is the Absence of God" - angels visit; some cured, some harmed, protagonist's wife is killed and he wants to go to heaven to be with her. another character is harmed then cured then harmed. storm-chasing the angels. didn't care about the characters

"Liking What You See: A Documentary" - perception of beauty; the Neanderthal who points out the next step will be suppressing appreciation for musical or athletic talent; and what about height? probably supposed to draw parallels to other PC situations. at the end, suggestions of software that will make speakers charismatic/effective. follows thwarted romance of a girl that grew up with calli, turned it off at 18, now wants to go back. referendum at the college. This was pretty interesting.

Sometimes it feels like the author is showing off knowledge in science or math areas - doesn't add much to the storyline.

Monday, April 27, 2020

Three Comrades (Erich Maria Remarque, 1936)

Book club selection (via Chris; session held (via Zoom) 24 April 2020).

Hadn't read this since 2011 (description here); I liked it even better this time around.

a favorite love story; cf'd to PJ - author got it right - the uncertainty in the early going, the mystery, the girl-part, the "that's sufficient" part

_______________

a favorite buddy story - the scene where Otto hands the pill to Robbie; the scene where Robbie thinks to contact Koster when needing help at the seashore; fundraising in what had to be a painful way

________________

WWI endlessly interesting in part because the soldiers had such a mind-blowing experience. of course it's hard to compare from war to war - but the jump in firepower and technology (gas, planes, etc.) relative to what soldiers were familiar with, and how tactics were used - not sure what would be like this. and they hadn't seen newsreels or really anything that would prepare visually.

survivors then come back to Weimar situation . . . after all the sacrifice and suffering (including home front folks like Pat) - no jobs, no hope

demagogues arise per usual

_________________

the spare writing style works for me - similar to All Quiet OTWF

Magic Mountain - sanitarium scenes

Saturday, April 04, 2020

Foundation Trilogy (Isaac Asimov, 1951, 1952, 1953)

Monday, March 16, 2020

Range - Why Generalists Triumph in a Specialized World (David Epstein, 2019)

Recommended by Nick Gales, who I suspect was interested in the topic as he and Maeve think about child-raising stuff.

Book primarily is taking a look at what's become conventional wisdom lately - the idea that focused training for a kid (10,000 hours or whatever) will yield results. Author argues that greater effectiveness is gained by folks with a broader "range". Not that we don't need the experts - we just need to recognize that - as knowledge-specialization inevitably gets deeper and deeper in each specialty area - there's more risk of tunnel vision.

Which I think we are seeing happening in the COVID-19 response (among plenty of other fails).

I liked this book, perhaps because it reinforces my priors? Could have been edited down quite a bit, however.

Tiger Woods early years compared to those of Phil Mickelson.

Interesting discussion about early specialization/focus for music students (author thinks it's overrated if not a negative).

He discussed Phil Tetlock and superforecasting - seems more bullish on all that than say twitter-tyrant Nassim Nicholas Taleb.

Good examples of specialist organizations getting stuck on a project, putting it out on the web, getting useful solutions from non-specialists. Maybe it seems obvious, but I think it's widely overlooked - grabbing additional perspectives works.

Sunday, March 08, 2020

Fortune's Distant Shores - A History of the Kotzebue Sound Gold Stampede (Chris Allan, 2019)

(159 pages)

(159 pages)Gift via Carol and Jim.

Book focuses on a window of a year or two where it was believed (entirely erroneously) that fortunes could be made mining gold in Kotzebue Sound (the name is familiar to us as our flight to Nome way back when had a short stop there - just north of the Arctic Circle).

I liked it - fascinating or almost exotic in that the story is remote in both time and geography - yet not so remote in either category - so it's possible if not easy to relate to folks getting caught up in a news cycle and wanting to have a go at gold mining.

Kotzebue as an alternative to the Klondike - where plenty of gold had been found, but there were some Canadian border issues for US citizens in particular. 49ers euphoria from California not so distant; plenty of appetite for this kind of thing, so a few well-placed stories go a long way.

Bernard Cogan ran ships up there and was a primary promoter - pretty clearly a crook. Makes money transporting suckers and their goods; then he goes whaling farther north to make some more money (perhaps the suckers should have noted that Cogan himself wasn't doing any mining).

Near-complete absence of gold - at best, enough for a hard-working miner to match wages that could have been earned in a much easier job back home - even suckers could figure this out pretty early and most don't bother with much digging; some return to the lower 48 within weeks or months, others are stuck through the winter. Interesting stories as they celebrate Christmas, fight scurvy and boredom, etc.

What wasn't funny: a significant number of deaths and illnesses, this is dangerous work and travel in a rough country, with most stampeders understandably un- or under-prepared.

Missionaries already in place in Alaska; the gold rush to this area accelerates the pace of changes for the locals - difficult in so many ways.

Author places significant reliance on diaries of an interesting fellow (named Grinnell) - he was primarily interested in birds, signed onto the gold-mining role as an excuse to do field work up north (but nonetheless seems to have done his tasks with the gold miners, such as they were).

Photos are a pleasure throughout the book - b/w, evocative.

After an ill-fated year - real gold strikes at Nome, so some move on to there - interesting background on Nome area at this time. A few continue to work the Kotzebue area notwithstanding no meaningful successes there.

Recommended.

Wednesday, February 26, 2020

The Brothers Ashkenazi (I.J. Singer, written 1933-35)

story takes place mid-19th century into mid 1920s

set primarily in Lodz; the town springs up from something of a village; much heavier Jewish concentration than most places; commercial and manufacturing center for textiles

Poland then part of Russia; Lodz merchants doing business throughout Russia; growth and change

twin Ashkenazi brothers - more detailed focus on Max - feverishly working to be #1 in the local industry (textiles); Jacob less talented, less intelligent, less diligent - but natural personality and physical gifts and unnaturally good luck

two other primary characters - Nissan and Tevye "The World Is Not Lawless" - work in local factories and seek to organize them; socialist speeches, Marxist dogma that would have sounded right at home in '20 presidential campaigns (complete with deeply religious strands)

all four leading characters working hard for entirely different things but in parallel ways and with similar results

all four leading characters from deeply Jewish backgrounds; changing but some retention

lots of character development including families of the four; earlier generation deeply traditional from the countryside/shtetl (typically relatively new to Lodz, it being a new town); Hasidic; rabbis with vast authority; this changes over time

some - certainly the Ashkenazi brothers - seek assimilation; not accepted but keep trying; as shocks such as economic downturn, war, inflation hit - guess who gets blamed

boom years in Lodz; then 1905 war with Japan; WWI; German occupation (shut down businesses, strip assets and ship west); Poles reassert themselves after Versailles treaty; part of the plot moves to Russia (during the 1917 revolution and thereafter - business couldn't be conducted during German occupation)

throughout - Jews tolerated to a point especially when useful, otherwise look out;

strand about considering Palestine

Buddenbrooks comparison, which makes sense

no way to assess accuracy - but much liked that Singer painted this detailed picture of what that world must have been like - the level of detail indicates he knew all about it

recommended - there's a lot going on here

Wednesday, February 19, 2020

The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, Volume III (Edward Gibbon, 1781)

Volume I addressed here.

Volume II addressed here.

Rankings are not easy, but I'm thinking Gibbon is definitely up there with my very favorites - Proust, Thomas Mann, Chekhov. I'll keep thinking about this. Gibbon's writing style really works for me. (Also he's the only one in this group who wrote in English, not sure what that tells me.)

This volume ends with the fall of Rome and the end of the western empire - dated here to 476 - concluding the more well-known part of Gibbon's work. (Volumes IV-VI pick up with the eastern empire through the fall of Constantinople).

This volume continues the themes from Volumes I and II - decline of civic virtue; transition from paganism to Christianity; emperor as a highly dangerous occupation; barbarian tribes moving to perimeter and then into heartlands of the empire, pushed from the east.

I keep thinking I've underrated Rome's accomplishments - a world of relative security and prosperity - sure it was selective, but isn't that always the case? Look at how Europe lived for centuries after Rome - cowering behind walls, ruined trade (therefore lost prosperity), lost technical skills, lost learning of all types.

Amazing that Christianity entirely supplanted paganism; this volume discusses the continuation of this process, all the way through formally outlawing paganism. Gibbon has quite the way of describing Christian hierarchy - sounding mild if not laudatory (to get past censorship) but absolutely skewering various folks.

He picks up on the martyrdom/relics scam and the many bad consequences - such a rac.ket.

Learned a bit about Ravenna - I hadn't realized that surrounding water features made it very difficult to capture (unlike Rome itself) - thus attractive to emperors in this days when "the army is our wall" no longer worked well. Not as difficult to capture as Constantinople.

Lots of discussion about the various barbarian tribes, what motivated them to migrate. Vandals in Africa; Visigoths taking southern France and into Spain; etc. Many were Arian. Then along comes the Huns - lots of discussion of Attila.

Down to Odoacer. Talk about "end of an era."

Monday, February 17, 2020

Furious Hours (Casey Cep, 2019)

Book club selection (via Nick; session held 16 February 2020).

Main hook here was Harper Lee - super trendy/popular right now in view of current politics - author researched a serial murder situation in Alabama that Lee - stuck for another hit after her one-time success - wanted to turn into another novel. But she wasn't able to finish it.

Some interesting stuff here about Alabama in those days, but the core concept wasn't enough to carry along a book.

Or maybe I'm the wrong person - I am baffled that anyone can ever be interested in crime stories, let alone serial murderers.

Harper Lee may have written a popular book, but it seems she had trouble with life in general - sudden wealth, unclear personal connections, landing in NYC (rather a foreign place), some alcohol issues, etc.

Connected from childhood with Truman Capote - another hook for the author - but doesn't really solve the issue about lacking a coherent story line.

Quick read.

Thursday, January 30, 2020

The Second Sleep (Robert Harris, 2019)

I like this author's writing style quite a bit (this one, for example).

Here, a young priest travels into a somewhat remote area west of London to attend to the burial of the local priest. The setting is a world reminiscent of the Middle Ages, but the time is hundreds of years after an unspecified apocalyptic event that caused devastation starting in early 21st century.

Knowledge of pre-deluge events is prohibited; technology is feared. But of course there are a few folks who insist on digging around, and get in trouble with the authorities (some of whom also are interested in digging around).

Young priest encounters impoverished noble lady; wealthy local interested in improving weaving technology; various others.

I liked the book; somewhat overlapped with (but didn't run nearly as interesting) as this one (which is among my very favorites).

Friday, January 17, 2020

The Complete Works of Isaac Babel (compilation 2002; mostly written early 1920s)

I keep seeing favorable references to Babel, but never read him before this. His biography is compelling - war correspondent (reminded me of Vasily Grossman) so lots of access - then he becomes disillusioned and out of favor. Rare, at least for me, reporting on the Red v. White (and other splinter groups) immediately following WWI. Early 1920s Russia hadn't yet implemented systematic censorship so his war reporting was more open, I think, than what Grossman could have done (Grossman had to do it via his smuggled-out book).

Babel eventually executed by Soviet regime.

I'll just mention a few of the categories in this quite-wonderful collection.

***

1920 Diary - perhaps my favorite war writing (and I've read lots of this)? Can't-miss content, and not even prep'd for publication (though this was basis for much of the Red Cavalry tales)

dense. highly effective . . . at least at the level of battles, skirmishes, movement between towns (cart transports. horses). towns taken and lost. confusion, exhaustion, merely finding food or forage. billets.

constant movement, constant commandeering of horses, provisions, shelter - locals get expert at hiding things

airplanes new - being used by the Poles - terrifying though not all that effective

just being tired, and depressed

interspersed with descriptions of age-old interactions - Poles and Jews, Cossacks, the borderlands, Galicia, shtetls, centuries of getting along and then sudden butchery. like forever.

Babel as "more like me" - bookish, not cut out for soldiering - but somehow finds himself right smack in the middle of everything - reminds of Vasily Grossman (Red Star writer)

little context is provided (as to what was going on in the larger political/military sphere, who was backing Poles - etc) - I think this heightens the immediacy of the war reporting, limits the distractions

running throughout - author as Jew - don't know if he tried to hide it, but he couldn't in any event. he feels connectedness to Jewish communities that he encounters. most in dire circumstances

the excitement around communism fading for Babel . . . he eventually characterizes as "fairy tales" the grand stories he tells locals as part of his job. as in all these settings, others are true believers and/or opportunists; discussing the International, worldwide uprisings, free everything (modern US politics might buy it, however)

***

Odessa stories - mostly about Jewish gangsters

***

Red Cavalry stories - genuinely excellent - but not quite as compelling to me as the raw notes in the 1920 Diary (though I read Red Cavalry first). One aspect here: Babel made the mistake of being too honest, naming commanders who were ineffective - several became leading figures in Soviet army, and they didn't forget.

**

Stories from Leningrad 1918 - just a few, great, raw

**

Stories from [Georgia?] - propaganda feel, I didn't like these very much.

Monday, January 13, 2020

Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind (Yuval Noah Harari, 2015)

Book club selection (via Rose; session held 12 January 2020). (PJ and I missed - colds.)

in general I very much like this type of book

not nec new, but a useful way of discussing man's rapid ascent - competitors had no time to adjust (see e.g. large animals in North America)

slower - more deeply wired - is the group-affinity, or tribalism - need to recognize how strong this is, not fear it; at the moment it's co-opted by politicians, community organizers, grant-seekers

hadn't thought about how cooking simplified digestion, or why humans went after marrow

my twitter feed is full of controversies about genetics - this gets into it but I don't understand

idea of the Cognitive Revolution - 70-30,000 years ago - use of language to rise up. the idea of myths and abstractions for groups >150

the ridiculousness of characterizing Peugot as a myth. it's a nexus of contracts. limited liability as something awesome . . . a simple way to encourage investment

similar for trade characterized as "fiction" = yes credit comes from credo

ridiculousness of forager societies as an ideal - the original affluent societies - come on "wholesome and varied diet"

faculty lounge discussion of ecological issues, capitalism in particular - yuck - bogeyman of economic growth; Adam Smith cliches

whining about how tough jobs are, how much work is required - come on

equality - look around your high school - nothing could be less natural (or more "myth")

trying to cover too much

but yes this is worth reading notwithstanding the above complaints