I read this novel at the gym in 30-minute sessions on the Stairmaster. So it took a little over two months. And well worth it. In addition to being a fantastic author, Tolstoy is a larger-than-life character in his own right.

I’m not sure how to compare, but many folks seem to think

Anna Karenina is Tolstoy’s greatest n

ovel. (It was published between 1875 and 1877, after

War and Peace and before he started getting preachy.) He takes 900+ pages going over seven main characters (Anna Karenina and Aleksey Karenin, Dolly and Stiva Oblansky, Konstantin Levin + Kitty, Vronsky) and, through them, revealing so many dimensions of married love, family life, the consequences of infidelity, and much more.

The most interesting character is probably Konstantin Levin (perhaps portrayed sympathetically because the character is so obviously based on Tolstoy himself, as

this biography by A.N. Wilson explains). Supposedly Tolstoy actually wrote expressions of love w

ith chalk on a tablecloth to his wife-to-be (just as Levin does with Kitty Shcherbatskaya). Like Levin, Tolstoy gave his diaries to his wife right after the wedding (though Tolstoy’s diaries caused much more disruption than the diaries in

Anna Karenina). Like Tolstoy, Levin is an aristocrat who enjoys working on his estate in the country rather than hanging around in Petersburg (or even Moscow) society. The deathbed scene involving Levin’s brother mirrors Tolstoy’s own brother’s death. Levin, like Tolstoy, tried to run schools for the peasants on his estate. Etc.

I understand that Levin didn’t even appear in the first draft of the story, which focused on the title character. The book was published in installments in a Russian magazine, and the story ran off in different directions over the course of several years. But the parts work.

Tolstoy has a way of making his characters ridiculously realistic. When reading his things, I constantly have the reaction “yes, that’s how people, including me, really think or feel about things.” His description of going to meet Kitty Shcherbatskaya at the skating rink when he was in

love with her but completely uncertain whether he “had a chance” is dead on. His descriptions of mowing hay with the peasants, the interactions with Kitty, the politicking among the Russian gentry, etc. are thoroughly enjoyable.

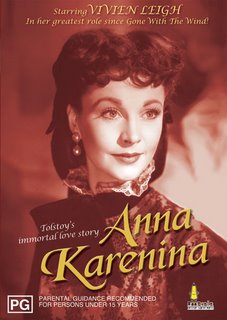

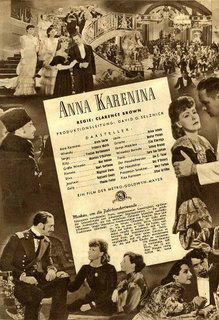

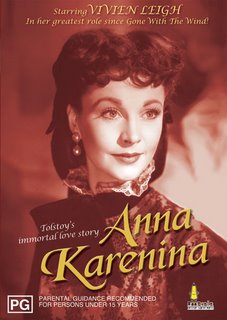

The novel has been filmed many times, typically with big-name leads. Details about the book are

here.

By the way, the novel begins with one of its most quoted lines, "Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way." A Tale of Two Cities, described

below, also had a pretty famous opening line ("It was the best of times, it was the worst of times").

hings etc. Lots of James' usual portrayals comparing and contrasting American and European ways (he lived on both sides of the Atlantic). In the end, I'm not a huge fan of his.

hings etc. Lots of James' usual portrayals comparing and contrasting American and European ways (he lived on both sides of the Atlantic). In the end, I'm not a huge fan of his.